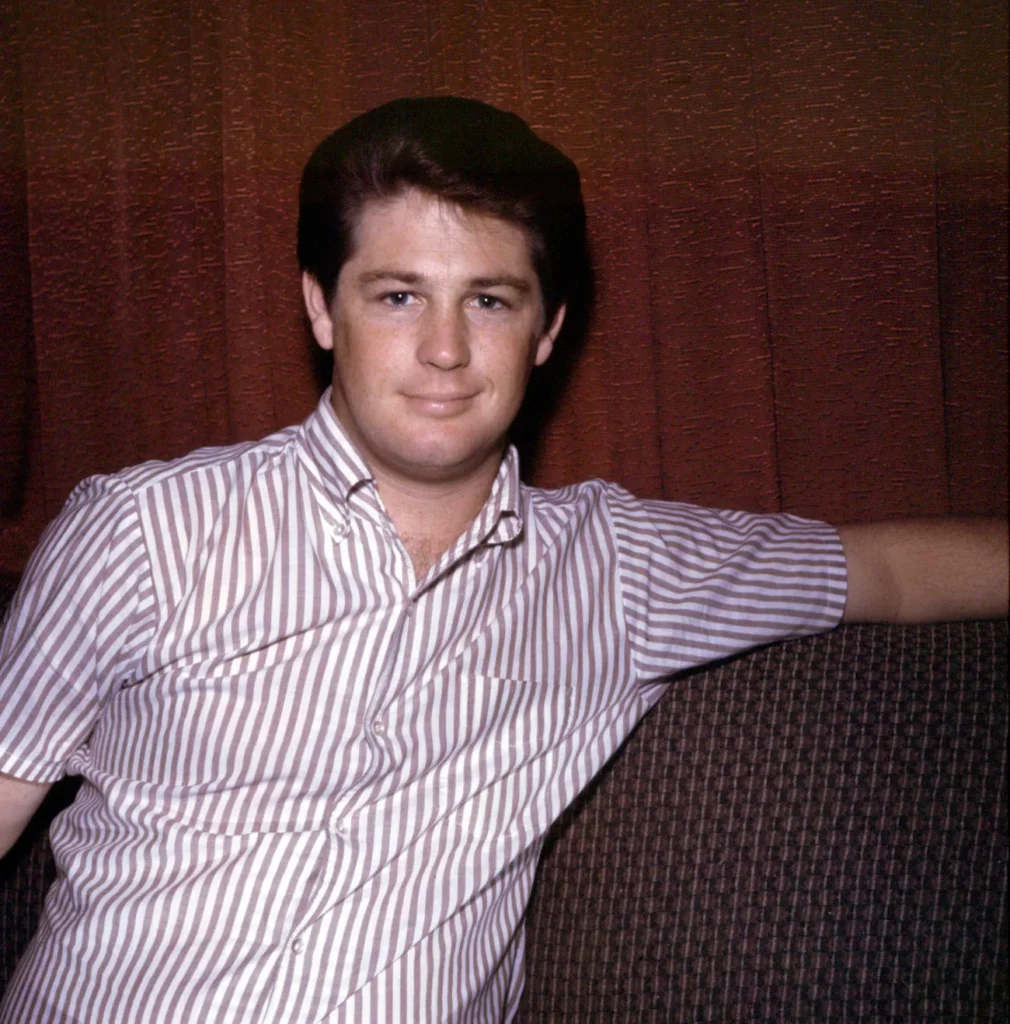

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Brian Wilson, who co-founded the iconic California band The Beach Boys and transformed teen pop into a poetic, modern musical form, has died at the age of 82.

Wilson’s family wrote in a statement on his website on Wednesday:

“We realize we are sharing our grief with the world.”

The most frequently quoted description of Wilson’s music was given by the artist himself when he, playing on a phrase coined by Phil Spector, declared that his goal was to “write a teenage symphony to God.” Based on the dreams of an ideal youth, his songs conveyed a vast ambition rooted in the belief that pop could be a medium of transcendence.

Outside the recording studio, where his mastery shone, Wilson struggled: as a child, he was abused by his father, and mental health issues—including auditory hallucinations (later diagnosed as schizoaffective disorder)—isolated him during the peak of The Beach Boys’ success. His greatest musical works made room for the profound sadness he experienced, while also capturing a nearly otherworldly beauty—a sunset glimpse into a soul yearning for peace.

That high quality was embedded even in the playful, light-hearted songs of the early Beach Boys. As one of the first major rock bands of the 1960s, The Beach Boys turned themes like drag racing, high school rivalries, and, of course, surfing into hits, expressing empowerment, freedom, and fun for many white middle-class kids as the postwar boom elevated their generation. Southern California became the mythical center of the new American dream—and Brian Wilson’s music became its soundtrack.

Keystone/Getty Images

A pop mind like no other

That playful, adventurous sound reflected Wilson’s childhood obsessions—jazz and doo-wop harmonies, and the work of American composers like George Gershwin. Growing up in Hawthorne, a working-class suburb of Los Angeles and an aerospace hub, Wilson became a student of music in his teens, spending hours with his record player, memorizing the harmonies of his favorite group, the Four Freshmen.

Like many teenagers, he and his brothers Carl and Dennis Wilson saw rock and roll as a path to social success. Their father Murry, an aspiring songwriter with abusive tendencies, saw his sons’ talent as a ticket to financial success. He managed their family band under the name The Beach Boys starting in 1961, until Brian separated from him following his first nervous breakdown in 1964.

Despite inner turmoil, Wilson quickly set a new musical standard for teen-oriented pop as The Beach Boys achieved national success with Capitol Records. The simplicity of early 1960s hits like “California Girls” and “I Get Around” was enriched by acoustic structures crafted by Wilson, drawing on jazz harmonies, American composers, and the emerging sound of Black pop from artists like Chuck Berry and girl groups.

By the mid-1960s, Wilson was pushing the boundaries of the three-minute pop song in ways few could imitate. The Beatles’ arrival in America in 1964 set the stage for what many fans considered one of pop music’s greatest friendly rivalries. Wilson and the Lennon-McCartney songwriting team constantly challenged and inspired each other, escalating with each competitive release.

Wilson’s genius peaks on ‘Pet Sounds’

Beatles producer George Martin called The Beach Boys’ 1966 album Pet Sounds an inspiration for The Beatles’ game-changing concept album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Wilson reportedly cried upon hearing “Strawberry Fields Forever,” saying, “They got there first.” But with Pet Sounds, Wilson had already arrived—an album that, nearly 60 years later, still stands as a dreamlike pinnacle of Top 40 pop.

Wilson was just 24 and already withdrawing from fame (he stopped touring with the band after his 1964 breakdown). Pet Sounds was his personal Moby Dick, a masterpiece demonstrating music’s emotional potential: 13 songs that critic Richard Goldstein described as “making loneliness an active pursuit,” performed by a group of L.A. studio musicians so skilled they were known as The Wrecking Crew, and layered with sound effects—barking dogs, rattling soda cans, crickets—all carefully produced by Wilson.

Rarely writing lyrics alone, Wilson collaborated with ad copywriter Tony Asher, whose words captured the liminal space between adolescence and adulthood—reflected in images like a surfer girl’s chopped-off hair in “Caroline, No” or the poignant declaration of “I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times.” Other Beach Boys followed Wilson’s piano-led instructions to deliver vocals that completed his vision.

In many ways, Pet Sounds was a solo project, with his bandmates more like orchestra members. Its intense introspection stemmed from Wilson’s worsening mental health, worsened by drug use and the feeling that the pop world that once empowered him no longer had room for his dreams.

Though Pet Sounds saw only modest success upon release, it is now widely considered one of the greatest albums of all time. (Rolling Stone magazine ranked it No. 2, just behind Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On.)

Wilson followed it with the 1966 single “Good Vibrations,” constructed through a revolutionary process: calling his favorite studio musicians for 17 sessions, gathering 90 hours of tape, and assembling the final song from pieces.

“You’d sit at a music stand with a blank sheet and wait until Brian gave you your notes, because he knew exactly what he wanted,” harmonica player Tommy Morgan told NPR in 2000. “He had every note in his head.”

“Good Vibrations” was both a critical and commercial success, signaling the full arrival of psychedelia for many listeners. But Wilson’s next project, Smile—a song cycle co-written with adventurous lyricist Van Dyke Parks—collapsed under the weight of Wilson’s perfectionism and the clash between his vision and the commercial concerns of his bandmates and label. A scaled-down version, Smiley Smile, was released in 1967. After decades of anticipation, Wilson completed Smile with new collaborators in 2004.

A retreat from public life

Legally bound to continue working with The Beach Boys under a new Reprise Records contract, Wilson withdrew even more in the 1970s. He briefly co-owned a health food store, Radiant Radish, and worked on demos at home, occasionally contributing to small Beach Boys hits. By 1973, he had become rock’s most famous recluse, rarely leaving his Bel Air home.

In the mid-’70s, Wilson’s then-wife Marilyn hired controversial therapist Eugene Landy—known for his “24-hour therapy”—to break Brian’s cycle of food and drug abuse, which had left him weighing over 300 pounds. Landy slowly took over Wilson’s life, becoming not only a controlling presence but also his manager and, in Wilson’s 1988 solo debut, a credited musical collaborator. The family intervened in 1991, ending their relationship.

Wilson’s second wife, Melinda, helped stabilize him. He began to heal and manage his mental illness, eventually growing strong enough to make a true comeback, collaborating with second- and third-generation power pop musicians like Andy Paley, Darian Sahanaja of The Wondermints, and producer Don Was. He reunited with The Beach Boys in 2012 for a tour and the album That’s Why God Made the Radio.

In his final years, Wilson—whose daughters Carnie and Wendy from his first marriage found pop success with the trio Wilson Phillips—cared for five adopted children with Melinda and pursued numerous projects, including the tribute album Brian Wilson Reimagines Gershwin, several highly collaborative solo albums, and regular touring that celebrated Pet Sounds and other Beach Boys classics.

After decades of mental health battles, Wilson appeared calm on stage and in interviews, enjoying the fame brought by his groundbreaking music and continuing to share a message of hope: that beauty and love can help heal even the most broken among us.